This isn’t really a Thanksgiving post.

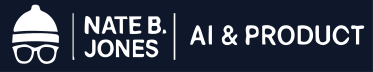

It’s a hard questions post. I’ve gotten a bundle of tough questions and I wanted to take a bit of a different approach in answering them.

Basically, I didn’t want to just give you my take. That’s only kinda useful. I wanted to equip you with prompts you could use to game out your OWN thinking in a structured way.

And I didn’t want to pull my punches. No strawmen here.

So I tackled hard questions like:

Will AI take everyone’s jobs?

Are students using AI to cheat?

Does AI consume too much water and energy?

Is AI-generated art “real” art?

Can you trust AI if it hallucinated on you before?

Will kids form unhealthy parasocial relationships with AI?

Is AI enabling surveillance capitalism / can we trust big tech with this?

Yes, you’ll get my take here, and you’ll get research to back it up. But more importantly you’ll get a chance to practice your OWN thinking by having structured conversations in your own LLM of choice with 6 different conversational personas:

Diane – High school English teacher watching AI erode the critical thinking she’s spent decades cultivating

Marcus – Paralegal whose job is actively being automated out from under him

Jennifer – IT director who’s seen three waves of “transformative” enterprise AI tools collect dust

Frank – Uncle who’s been reading about surveillance capitalism and doesn’t trust any of it

Maya – Climate-conscious Gen Z cousin tired of Silicon Valley breaking things

James – Wants to talk about what makes us human

If you’re wondering how I came up with these, well they’re based on my family, extended family, and circle of friends. Names changed to protect the innocent/guilty.

I have to have these conversations around the Thanksgiving table too, so I thought I’d share the way I think about it, and hopefully that’s helpful!

For those in the US, enjoy your celebration today. For those outside the US, it’s like the one time we have a holiday and the rest of the world doesn’t lol

Grab the 6 Conversational Practice Prompts

I built six practice conversations to help you prepare. Each one puts you across the table from a different skeptic—not strawmen, but people with real concerns rooted in heartfelt values.

Diane is the high school English teacher watching AI erode the critical thinking she’s spent decades cultivating. Marcus is the paralegal whose job is actively being automated out from under him. Jennifer is the IT director who’s seen three waves of “transformative” enterprise AI tools collect dust.

Meanwhile, Frank is your uncle who’s been reading about surveillance capitalism and doesn’t trust any of it. Maya is the climate-conscious Gen Z cousin who’s tired of Silicon Valley breaking things. Pastor James wants to talk about what makes us human.

Each conversation adjusts based on how you approach it—validate their concerns and they’ll open up; lecture them and they’ll dig in. The goal isn’t to win. It’s to practice the rhythm of listening, acknowledging, and exploring together.

How to Talk About AI at Thanksgiving Without Starting a Fight (Or Just Passing the Stuffing)

You’re sitting at Thanksgiving dinner. Someone brings up AI. You can feel the shift.

Your uncle’s convinced it’s coming for everyone’s job. Your cousin read something about kids using it to cheat on essays. Your aunt’s furious about an article on water consumption. You’ve got two options: pivot to literally any other topic, or actually engage.

Most people pick option one, and honestly, I don’t blame them. But if you’re going to try option two—if you actually want a real conversation instead of parallel monologues over turkey—it helps to know what you’re walking into.

That’s what this piece is for. I’ve put together some frameworks for thinking through these conversations, a fact sheet with actual numbers you can reference, and a set of practice prompts so you can game out the hard conversations before they happen. (The practice tool is at the end—it lets you simulate different scenarios and test your responses.)

One thing upfront: I’m not trying to give you ammunition to win arguments. These concerns your relatives have? Many of them are legitimate. Students really are using AI to cheat. Data centers really do consume significant resources. I’m not here to tell you those worries are unfounded—I’m here to help you have honest conversations about genuinely complex issues where the evidence points in multiple directions at once.

Why Facts Alone Don’t Work

Here’s what I’ve learned from these conversations in my own family: when you start fact-checking AI claims, you’re arguing about specifics—data center energy use, token costs, model capabilities. But that’s rarely what’s actually happening underneath.

Psychologist Jonathan Haidt has this theory about how we argue. On the surface, we’re debating policies and facts. Underneath, we’re defending core moral values—fairness, authenticity, protection of the vulnerable. When AI bumps into one of those values, that’s the real source of the objection.

I’m not saying the facts don’t matter. They do—that’s why I’ve included a fact sheet below. But understanding why someone cares about a particular issue helps you have a conversation instead of a debate.

The water-use conversation has turned into an annual tradition in my family at this point. I have a cluster of relatives from Portland who are convinced AI is eating water left and right. When I’ve shown them actual numbers, they’ve rolled their eyes and insisted it’s all a Microsoft plot. There’s a trust layer embedded in the objection—distrust of big tech, distrust of corporate data—that sits underneath anything factual I try to offer. When someone has already decided the numbers are rigged, the numbers won’t move them.

Same thing with the educators in my family. For them, AI isn’t abstract—it’s showing up in homework assignments right now. Kids using it to do work they should be learning. They see the shortcuts every day. And they’re not wrong to be concerned: roughly 43% of college students have used AI tools for coursework, with the majority using it for homework and essays. UK universities saw AI-related cheating cases triple in one year. This isn’t paranoia. It’s pattern recognition from people on the front lines.

And then there are my Florida relatives who are convinced kids will form parasocial crushes on AI or get pushed toward disordered behavior. That one felt overblown to me until I saw the research—there’s genuine evidence that vulnerable populations, especially adolescents with preexisting mental health conditions, face real risks from intense AI relationships. “Parasocial” is Cambridge Dictionary’s word of the year for 2025. This isn’t hypothetical anymore.

My goal in these conversations isn’t to convince anyone that AI is great. It’s simpler: can I help someone move from automatic rejection to genuine curiosity? Can I model the kind of honest engagement where we acknowledge what’s real and uncertain together? That’s the whole game.

The Conversations You’re Likely to Have

On Jobs

Here’s where I think most of the discourse goes wrong: economists assess AI’s impact on jobs by looking at tasks. They break down a role into component activities, measure which ones AI can perform, and project displacement. On paper, this makes sense. In practice, jobs aren’t task bundles.

The radiology example makes this concrete. AI imaging systems now outperform most radiologists on specific diagnostic tasks. If jobs were just tasks, radiology positions should be cratering. Instead, radiology jobs are growing. Why? Because the job involves patient interaction, clinical judgment, integration with care teams, liability, trust—none of which the task analysis captures.

This pattern repeats across fields. Benchmarks like GDPVal show that AI is just starting to perform adequate work at the task level—and there’s an enormous gap between adequate task performance and replacing a job. Most economic projections skip that gap entirely.

The jobs genuinely at risk are the ones that were already at risk: judgment-free back-office automations that are essentially data entry. Those roles have been vulnerable to automation for decades. AI accelerates that existing trend, but it’s not a new category of displacement.

What I try to convey in conversation: “The task-level analysis looks scary, but jobs aren’t just task lists. Radiologists have AI that outperforms them on diagnosis, and radiology hiring is up. The gap between ‘AI can do this task’ and ‘AI replaces this job’ is much bigger than the headlines suggest. The roles actually disappearing are back-office data-entry type work—and honestly, those have been shrinking to automation since before ChatGPT existed.”

That said, I don’t want to dismiss the concern entirely. Early-career workers in AI-exposed occupations have seen a 13% employment decline—that’s real, even if the aggregate numbers look stable. And whether we get more augmentation (AI amplifying what humans can do) or more automation (AI replacing humans) depends on choices companies and policymakers make. It’s not predetermined. I want a world where AI makes my doctor better at diagnosis, not one where AI replaces my doctor. Both futures are possible.

On Cheating and Education

Your teacher relatives aren’t imagining this. The numbers are real: 43% of college students have used AI tools, with 89% using them for homework. UK universities caught nearly 7,000 students cheating with AI in 2023-24—triple the prior year—and experts say that’s a severe undercount. In one test at the University of Reading, 94% of AI-written submissions went undetected.

But here’s important context: Stanford’s long-running research on academic dishonesty found that 60-70% of high school students reported cheating in some form before ChatGPT existed. The tools change. The behavior doesn’t seem to have spiked as dramatically as headlines suggest.

The more honest conversation might be: “Yeah, this is a real problem. Kids are using AI to skip the learning. Maybe we need to think about AI the way we think about calculators—they changed what we teach, not whether we teach. We stopped drilling arithmetic and started teaching mathematical thinking. Maybe that’s the shift here too. But we haven’t figured out the rules yet, and I get why that’s frustrating.”

The calculator parallel isn’t just rhetoric. In the mid-1970s, 72% of teachers and mathematicians opposed letting seventh graders use calculators. Critics worried it would undermine basic skills and create machine dependency. The debate lasted decades. We figured it out eventually, but it took deliberate work—not just letting technology wash over education.

On Water and Energy

The framing problem here is that AI gets compared to individual homes. “A data center uses as much water as 6,500 households!” That sounds alarming until you realize you’re comparing an industry to a household. The comparison is structurally broken.

When you benchmark AI against other industries—which is the appropriate comparison—the picture changes entirely. U.S. golf courses consumed roughly 547 billion gallons of water in 2020. Google’s entire global data center footprint used about 6.4 billion gallons in 2023—roughly one-eightieth of what golf courses use. Leaking faucets in American homes waste approximately 1 trillion gallons annually. That’s nearly seven times what all data centers globally consume.

This doesn’t make AI’s resource consumption irrelevant. But it means AI should be evaluated the way we evaluate any industry: is what we’re getting worth what we’re spending? That’s a legitimate question. “AI uses more water than your house” is not a legitimate framing—your house isn’t an industry.

On electricity, OpenAI disclosed that the average ChatGPT query uses about 0.34 watt-hours—roughly what a lightbulb uses in a couple minutes. That’s several orders of magnitude less than early estimates suggested. But with 400 million weekly users, it adds up. Projections suggest U.S. AI and data centers may consume 6-12% of total U.S. electricity by 2028.

What I usually say: “The water thing is real, but the framing is off. Comparing an industry to a household makes everything look catastrophic. Compare AI to other industries and it looks different. Golf courses use about eighty-five times more water than Google’s entire global data center operation. Leaky pipes in American homes waste nearly seven times what all data centers globally consume. AI should be held accountable like any industry—but it should be compared to industries, not to your kitchen sink.”

On AI Art and Authenticity

When someone says AI-generated art isn’t real art, they’re protecting something important—the idea that human struggle and intention matter, that there’s something sacred about creative expression that can’t be mass-produced.

I feel that too. The books on my shelves weren’t written by ChatGPT. And 76% of Americans agree that AI-generated work shouldn’t be called “art.”

But here’s what complicates my thinking: in blind tests, people can’t reliably distinguish AI-generated images from human-created ones. When shown individual artworks, participants with backgrounds in cognitive science and computer science performed no better than random guessing. We value the human struggle, but we can’t actually detect its presence in the output.

The photography parallel feels relevant. When cameras appeared in the mid-1800s, the consensus was that photographs could never be art—they were mechanical reproduction, not human expression. Portrait painters saw their businesses collapse overnight. It took nearly a century for photography to be fully accepted as an art form. That doesn’t mean AI art is equivalent, but it suggests we’ve been here before with authenticity concerns about new creative technologies.

What I usually say: “I think about AI more like a camera than a painter. Cameras made capturing images instant, but we still value paintings for the human intention behind them. AI might be the quick photo. Human work stays the oil painting. But I’m honestly not sure where the lines will settle.”

The “Beta Tester” Problem

People often judge AI based on the version they tried months ago. It hallucinated, gave them bad information, felt unreliable. They wrote the whole thing off.

They’re not wrong about the limitations. But research shows hallucination rates decline about 3 percentage points per year, and models improve dramatically between versions. ChatGPT 3.5 produced hallucinated references 40% of the time; ChatGPT 4 dropped that to 29%. Current models are substantially better still.

Evaluating AI based on last year’s ChatGPT is like judging the internet based on dial-up in 1994. The dial-up complaints were valid. The conclusion that the internet would always be that way was not.

If someone seems stuck on an old experience, the bonus move is to actually pull out your phone and show them what current versions can do. Real experience beats theoretical discussion. Maybe help figure out dessert or build a quick family trivia game—something tied to the holiday that doesn’t feel like a demo.

What I’m Actually Trying to Do

I want to be clear about my goal here, because I don’t want this to come across as manipulation tactics.

I’m not trying to convert anyone to loving AI. I have genuine uncertainty about how a lot of this plays out. The parasocial relationship research worries me. The environmental footprint is real. The education system is genuinely struggling to adapt.

What I’m trying to do is model a different kind of conversation—one where we acknowledge the concerns are legitimate, look at what the evidence actually shows (including where it’s mixed or uncertain), and explore together rather than debate. If your relatives leave the conversation feeling heard and maybe a little curious, that’s a win. If they leave feeling lectured or dismissed, that’s a failure regardless of how good your facts were.

The pattern that works for me: listen for what they’re protecting, validate it honestly (because it usually deserves validation), share what you see in the data including the uncertainties, and invite them to explore with you. Then maybe pull out your phone and do something useful together.

What bombs: throwing studies at people, getting defensive, treating concerns as ignorance, trying to win on pure logic.

Your relatives probably have solid reasons for their concerns. Most of what they’ve heard came from journalists who are themselves uncertain about AI. They’re getting worst-case scenarios from sources they generally trust. You’re not smarter than them. You just have different information and maybe more time spent with the technology. Start by respecting that.

Fact Sheet: Numbers You Can Reference

Jobs

Jobs ≠ tasks: AI outperforms radiologists on diagnostic tasks, yet radiology hiring is growing

Benchmarks like GDPVal show AI is just reaching adequate task-level performance—job replacement requires far more

Jobs most at risk: judgment-free back-office automation (essentially data entry)—these have been vulnerable to automation for years

Early-career workers in AI-exposed occupations saw 13% employment decline (Stanford)

77% of employers plan to prioritize reskilling by 2030

Education

43% of college students have used AI tools; 89% for homework, 53% for essays

UK university AI cheating cases tripled year-over-year (5.1 per 1,000 students)

60-70% of high school students reported cheating before ChatGPT existed (Stanford)

68% of teachers now use AI detection tools; these tools have significant false positive rates

Water and Energy

The framing problem: AI gets compared to households, but AI is an industry

Golf courses: ~547 billion gallons (2020)

Google’s global data center footprint: ~6.4 billion gallons (2023)—roughly 1/85th of golf course consumption

Leaking faucets in U.S. homes: ~1 trillion gallons wasted annually—nearly 7x global data center consumption

Average ChatGPT query: 0.34 watt-hours (per OpenAI, June 2025)

Projected AI/data center electricity: 6-12% of U.S. total by 2028

AI Art

76% of Americans don’t believe AI-generated work should be called “art”

In blind tests, people perform at chance level distinguishing AI from human art

Artists who adopt AI tools see 25% productivity increase, 50% increase in favorites

Trust

Global trust in AI companies: 53% (down from 61% five years ago)

U.S. trust: 35% (down from 50%)

47% of Americans expect AI will negatively affect society (up from 34% in December 2024)

Among weekly AI users: 51% positive, 27% negative

Practice Prompts

Before the big dinner, you might want to run through some scenarios. Here’s a tool that lets you practice—it’ll throw common objections at you and help you develop responses that feel natural rather than scripted.

Grab those 6 conversational prompts

Try a few rounds with different framings. The goal isn’t to memorize answers—it’s to get comfortable with the rhythm of acknowledge-explore-invite that makes these conversations work.

The Real Talk

These conversations are going to be messy. They’ll jump topics. Someone will derail mid-thought. Your uncle will tell a tangential story. The gravy boat will arrive at the wrong moment.

That’s completely fine. You’re not delivering a presentation. You’re having a conversation with people you care about.

Success looks modest: someone asks to see what current AI can do. Someone says “I didn’t realize that.” Someone mentions looking into it more. The conversation stays warm. Nobody leaves angry.

If this feels too complicated, you have full permission to change the subject. Not every moment needs to be productive. Sometimes stuffing and small talk is the exact right choice.

But if you do engage, remember: your relatives likely have good reasons for thinking the way they do. Many of their concerns are backed by real data. Start there. Respect that. Then see if you can crack the door open to curiosity—in both directions.

Pass the mashed potatoes. Maybe learn something from each other about AI.

That’s about as much as you can ask for (that and a turkey that isn’t too dry).